“One way to meet new people is to listen more carefully to the people you see every day.”

– Robert Brault

As I sat on an airplane and came across an Ad Age ‘interview’ of advertising legend Bill Bernbach, the thought crossed my mind, ‘How would one respond to these questions in the context of the 21st century?’. It proved to be a beneficial exercise for professional reflection – by no means am I setting myself on a pedestal beside the likes of Bernbach – rather, responding became a means to clarify my own perspective. I highly suggest giving this approach a try the next time you find yourself waiting in a terminal or stuck in the middle seat of a plane.

We can glean much from Bernbach – he was named the single most influential person in advertising in the 20th century by Ad Age, but unlike others in the industry, Mr. Bernbach didn’t leave behind an opus in book form. So David Andrew Lloyd took it upon himself to track down the man and “interview” him.

In Search of Bernbach, Advertising’s Greatest Thinker

By: David Andrew Lloyd

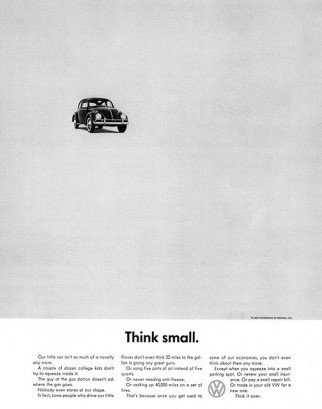

To learn the secret behind such classics as his Volkswagen “Think Small” ads and Avis “We Try Harder” campaign, I decided I must find Bill Bernbach, the leading force behind the Creative Revolution.

He had the ability to analyze a product’s qualities, and extract its raw personal emotion. He knew a place where he could actually touch the human soul.

With his American Tourister Gorilla as my guide, we traveled over the Mountain of Focus Group Research, through the dark Jungle of Behavioral Sciences and past the Tomb of the Unknown Edsel. Eventually, we found Bernbach in the Valley of Intuition, celebrating his 100th birthday.*

LLOYD: What’s the key element for developing effective advertising?

BERNBACH: The purpose of advertising … is to sell. If that goal doesn’t permeate every idea you get, every word you write, every picture you take, you’re phony, and you ought to get out of the business.

HEIDEMANN: This has not changed; we are here to help our clients drive revenue.

LLOYD: Then how did you justify your radical style of showing empty bottles in ads, teeth marks in Levy’s bread, models without smiles?

BERNBACH: I realized that the growth of television, along with all the existing media, would result in consumers being bombarded with more messages than they could absorb. So the advertiser would have to deliver his message in a different way — memorably and artfully — if he was going to be “chosen” by the consumer.

HEIDEMANN: Ironically, Bernbach’s prediction couldn’t be more true. The proliferation of channels and the distribution of content has only made it more difficult to reach the consumer. Now the consumer has access to information and peer review through social channels that were not possible 10 years ago. This means that content, the style, and type are more important than ever, while the one too many models in which the zeitgeist of the masses was the defining characteristic of success that now needs to be delivered to an audience or segment level.

LLOYD: What was wrong with the old scientific approach?

BERNBACH: I warn you against believing that advertising is a science. Artistry is what counts. The business is filled with great technicians, and unfortunately they talk the best game … but there’s one little problem. Advertising happens to be an art, not a science.

HEIDEMANN: The artistry now is in the experience and not just the message or the content. We need to craft experiences that are contextually appropriate whether that is in the context of a device, channel or the customer’s state of mind.

LLOYD: Sounds blasphemous.

BERNBACH: The more you research, the more you play it safe, and the more you waste money. Research inevitably leads to conformity.

HEIDEMANN: In an emerging market in which technology is a disruptive force, research only gives you the rearview mirror. In today’s age, innovating around the experience requires agility and artistry.

LLOYD: At least you won’t offend anyone.

BERNBACH: (Laughing) Eighty-five percent of all ads don’t even get looked at. Think of it! You and I are the most extravagant people in the world. Who else is spending billions of dollars and getting absolutely nothing in return? We were worried about whether or not the American public loves us. They don’t even hate us. They just ignore us.

HEIDEMANN: Those numbers are getting smaller and smaller over time. Interestingly, the opportunity to connect is getting larger. Customers are expressing their preferences in more and more specific ways. The ability to deliver experiences and content that are meaningful and relevant will materially impact the engagement of an audience.

LLOYD: So how do you get into that desirable 15%?

BERNBACH: The only difference is an intangible thing that businessmen are so suspicious of, this thing called artistry. … Try riding the bus … and you just watch the people with Life magazine flipping through the pages at $60,000 a page, and not stopping and looking. The only thing that can stop them is this thing called artistry that says, “Stop, look, this is interesting.”

HEIDEMANN: By taking the time to understand consumers at an audience or segment level we have the opportunity to develop experiences and content that exactly meets their needs. No longer do we need to broadcast one-size-fits-all messaging we can speak to customers as individuals.

LLOYD: Shouldn’t market research improve those odds?

BERNBACH: Research can be dangerous. It should give you facts and not make judgments for you… We are too busy measuring public opinion that we forget we can mold it.

HEIDEMANN: Research should be a measure of efficacy and a model for improving the connection between audiences. In today’s world, taking the time to truly understand the expectations and desires of an audience is where research is valuable. In this way, we can begin to craft and refine experiences that are considered relevant.

LLOYD: Advertisers still need to judge their ideas against something tangible.

BERNBACH: I have found, by and large — I know this is heresy — the better the marketing man, the poorer the judge of an ad. That’s because he wants to be sure of everything, and you can’t be sure of everything.

HEIDEMANN: We live in a world of measurement in which the quality of the experience and the content can be measured. Gone are the days when we had an opaque understanding of the efficacy of our advertising, now we can measure to the exact expected business outcome.

LLOYD: Doesn’t it seem logical to test your ads?

BERNBACH: (Grinning.) I’m beginning to believe, incidentally, that logic is one of the great obstacles to progress.

HEIDEMANN: Now that Branding, Experiences and Content can be modified with relative ease, the 21st-century model requires constant attenuation and experimentation. We need to test, but more importantly, we need processes by which we measure and methodically improve the experience by audience.

LLOYD: How do you suggest advertisers make their “guesses” accurate?

BERNBACH: Know his product inside and out. Your cleverness must stem from knowledge of the product. … It’s hard to write well about something you know little about.

HEIDEMANN: Again in the 21st-century model, it’s true that you need as much product knowledge as you can accumulate, however, it is as important or more important that you understand your audience.

LLOYD: Ha! That’s research. Why can’t you admit advertising is a science?

BERNBACH: (Annoyed.) The greatest advances in the history of science came from scientists’ intuition. Listen to one of the greatest scientific minds talking on the subject of physicists. “The supreme task of the physicist is to arrive at those universal elementary laws from which the cosmos can be built up by pure deduction. There is no logical path to these laws. Only intuition can reach them.” The scientist’s name was Albert Einstein, the greatest scientist of them all!

HEIDEMANN: Since the beginning of time, the experience matters and the experiences should be different for each of us.

LLOYD: Nevertheless, clients want to feel secure before spending their money.

BERNBACH: In advertising the big problem facing the client is that he wants to be sure that his new campaign is foolproof. Even we can’t be sure that there are certain things that an ad must contain. They are no more predictable than that a play will be a hit or a book a best seller.

HEIDEMANN: We help companies fish; but mostly we are teaching them how to fish. They spent decades building institutional models of how to drive business which has been significantly disrupted by technology, now they need to learn how to integrate these new capabilities into their business and organizational models.

LLOYD: Can you blame them for being cautious?

BERNBACH: Playing it safe can be the most dangerous thing you can do.

HEIDEMANN: We live in a time of disruption and an opportunity to gain lasting strategic advantages.

LLOYD: It’s their money. It’s their right to make that decision.

BERNBACH: We don’t permit the client to give us ground rules. It’s bad for the client.

LLOYD: Come on, Bill. That’s a bit egotistical.

BERNBACH: I don’t mean to be arrogant, but we have deep convictions about our work, and we believe that one of the greatest services we can give the client is to honestly state our convictions.

HEIDEMANN: I couldn’t agree more – Our clients hire us to give them the honest truth, 100 percent, and just like any relationship, it requires both parties to be forthcoming.

*Answers are actual Bernbach quotes.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

David Andrew Lloyd is a third-generation Bernbachian. His first boss, Chuck Bua, a five-time Clio Award winner, worked under Bernbach at DDB. Lloyd now lives in Studio City where he writes film and TV comedy — because that’s all he can take seriously.

Read the full article on Advertising Age